How the Internet broke the self

2/3 Hall of Mirrors: Digital personae and the fractured dividual

“The medium is the message” - Marshall McLuhan

Previously, we applied the Deleuzian concept of multiplicity to the notion of the self and explored how the self is not unified, but stretches across different dimensions and includes different parts. We now turn to understanding the internet as a medium of multiplicity.

The current internet consists of multiple overlapping platforms: social media networks, digital commerce, educational environments, and entire immersive worlds for entertainment. A digital persona can be thought of as a repetition of a part of the self within a specific platform. Everyone will agree that our digital personae can never capture the complex, living reality of our existence. What may not be clear is the how and why. Applying the thinking of Marshall McLuhan illuminates the mechanisms at work. We will explore how the medium of the internet and its different platforms produce different personae.

The message is multiplying

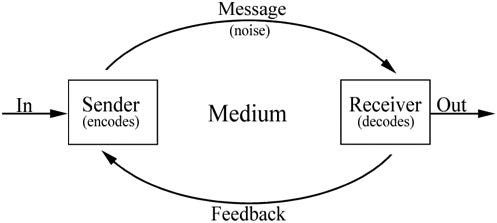

Let’s first turn to the internet as a medium before looking at how it impacts our notion of the self. As gestured towards by McLuhan’s bumper sticker “The medium is the message”, the medium where any communication takes place shapes the communication in important ways. The same person’s thoughts, beliefs, and behaviours change significantly as they interact over different media. According to McLuhan, the medium of the printing press created a shift towards individualism and rationality, while the medium of television encouraged passive, isolated viewing, while creating a sense of global interconnectedness.

Applying this to the internet, what is the message of cat videos, memes, and cookie-consent pop-ups? A few key characteristics: While audio-visual, short-form media tends to dominate, we find all types of previous media on the internet: the book, the radio, television etc. all reincarnate in cyberspace. The internet supports instantaneous communication, resulting in an increased speed of interaction. The interactivity also leads to more repetition, remixing, and recombination: like an infinite game of “telephone”, messages morph and propagate through the interwebs. Think memes and “copypasta”. Communication on most media is many-to-many and global, as illustrated by the notion of “tweeting in public”. This feature erases the notion of geographic distance - cyberspace is flat.

Finally and crucially, the public nature of communication online adds an imagined audience to any interaction: We care about second-order observation online, how others are viewing our interactions, and carefully curate our profiles accordingly. Hans-Georg Moeller describes this as “profilicity”, a new paradigm of identity after authenticity and sincerity. These properties of online media shape our sense of self across platforms.

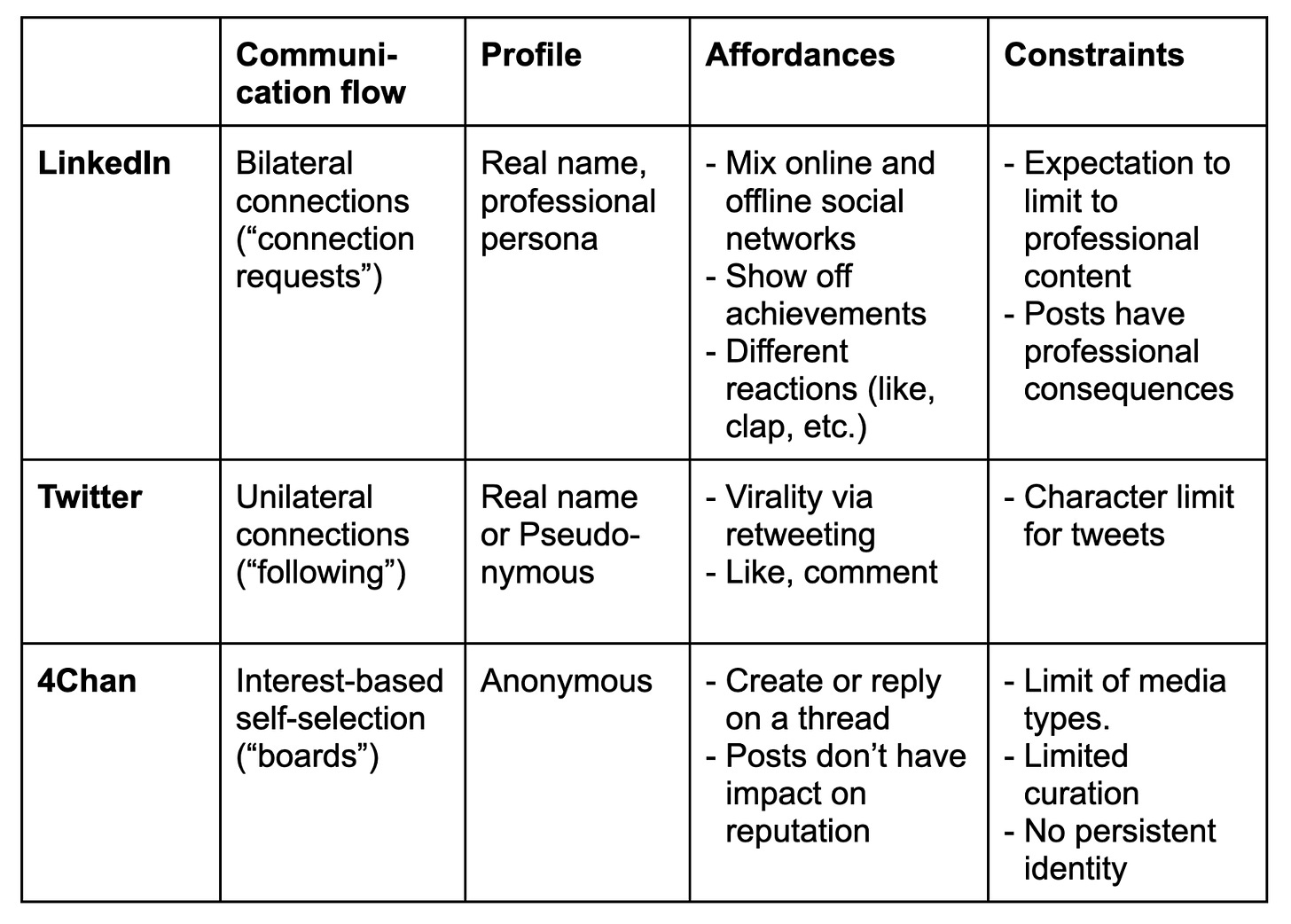

However, the internet is not just a single new medium, but a multiplicity of media. Each platform is a medium. Understanding how different media platforms shape communication within them allows us to draw key conclusions for our personae on them. The same message is expressed and received starkly differently on different media platforms - this illustrates how “the medium is the message”. LinkedIn, Twitter, and 4Chan cover a broad range and exemplify how communication changes across platforms. The key dimensions to look at are how communications flow, what type of profile is supported, as well as affordances and constraints.

The table below lists the key features of the 3 platforms:

The real-world profile and professional social graph explain why LinkedIn is full of humble brags and water-cooler trivialities. The virality afforded by Twitter and its constraints around character limits explains why it’s like an infinite cocktail party where everyone is shouting scissor statements. Finally, it seems obvious that the anonymity and lack of persistent identity on 4Chan would produce a dark, alien hive-mind with an obsession with breaking social conventions.

How Twitter works (e.g. character limit, optional pseudonymity, virality) is more important in shaping the messages received than the actual content in any Tweet or the person tweeting it. Whatever message the Tweeter wanted to convey would be received in an entirely different manner if it was posted on LinkedIn or 4Chan, since the medium alters the message. Affordances and constraints of the medium also limit what is possible to say in the first place.

The proliferation of messages and media is exponential because there are also dense connections between platforms: A viral Tik Tok video can be cross-posted on Instagram, get commented on Twitter, while being compiled into a Youtube playlist, all at the same time.

Another way of understanding “the medium is the message” is as a distillation of the current cultural moment: from a historical perspective, the emergence of Social Media says much more about the culture that gave rise to it than all posts across its many platforms. The frenetic differentiation and recombination of media on the internet is turning the previously seemingly linear progression of culture and history into a James Joyce novel. Rhizomatic multiplication, remixing, and repetition is the message of the Internet.

The fracturing of personae across the digital sphere

“There is a crack, a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in” - Leonard Cohen

What happens when the internet's multiplicity collides with the self's multiplicity? What does it mean to be a self (i.e. different personae) in the digital age?

Here is the key insight:

The self is fractured along the breaks between platforms.

Repetitions across platforms become different enough to lose their apparent identity. As a result, we find ourselves with a persona, a different sense of self across platforms; resulting in an “Insta-persona” and a “Twitter-persona”. Different parts align themselves with breaks in media, merging with the persona most in line with those perspectives and stories. For instance, a proud part will find itself most happy on LinkedIn while some angry part clearly finds their home on Twitter or even 4Chan (if it’s really angry).

Deleuze proposes the notion of a “dividual” (instead of “individual”) to highlight the divided nature of the self along different lines of power. We’ve moved from individuals shaped by institutions (what Foucault called “disciplinary society”) to ever-changing dividuals controlled by the platforms they are on. It is in Deleuze’s “Postscript on the Societies of Control” that the term “dividual” is proposed, also explaining how we are passing from “Discipline” to “Control”.

The term "control" refers to covert power, while "discipline" refers to overt power, direct (often bodily) coercion. Even though there are more “violent” instances of platform control like banning accounts and revoking access, most of it is very subtle and barely noticeable. Control lies in the specific ways platforms regulate data flows and power: How dividuals connect on any given platform (“friends” vs. “following” vs. “boards”), what they know about each other (IRL identities vs. pseudonymous or anonymous), how messages spread and are curated, as well as the myriad of other small decisions. The real censorship is the subtle kind found in the choice architectures, which are brought about by the affordances and limitations of platforms. These more subtle forms of violence, almost invisible, are harder to oppose than the blunt bodily coercion of disciplinary societies. The self is fractured into different personae across breaks between platforms as a result of the differences in the control structures and forms of subtle violence they exert.

Just like the different threats of violence in disciplinary society created distinct roles like “worker”, “father”, “student”, and “patient”, etc. platforms create threats of subtle violence for the persona. The LinkedIn persona is not posting a controversial take out of fear of not being perceived as “professional”; the Twitter persona is pithy and slightly polarising to minimize the chances of being “ratioed”. These decisions are not made consciously, they are inherent in the persona itself.

However, there is an even more fundamental break that occurs to the self online: it disembodies you. Out of the four dimensions of self (social, narrative, perspectival, bodily - see the previous article), it seems that only the social and narrative dimensions of the self have found their way into the digital. The perspectival and bodily selves (for now), have largely been left behind. As a result, the complex feedback loops between all dimensions of the self are disrupted. The social and narrative dimensions of the self get entangled with the internet. This produces a range of dividuals that both have accelerating feedback loops between them and are cut off from other dimensions of the self. The perspectival and bodily dimensions of self connect us with our physical environments, and the actual world around us. Losing those dimensions led to selves that are disembodied and flattened.

The digital kaleidoscope

However detailed and data-rich, the digital personae we create can only ever be a flat image. Constrained by the platform each persona lives on, and always reflected in the imagined gaze of an audience, the different personae form a kaleidoscope of projected images. We can speculate that the flows between dimensions of the self are changed radically in the digital age: selfing now happens on the social-narrative dimensions, often cut off from the perspectival-bodily. The self in the digital at once multiplies and is flattened. We trade more personae with more flexibility and speed of expression for a loss of dimension of the self.

In the next article, we will further explore the implications of these insights around the fracturing of the dividual across media lines. We will explore what this means for our notion of identity, for our ideal of health, as well as for the culture at large. The final piece of the series will speculate that identity in the digital realm increasingly becomes a toy, a weapon, and an object of desire.