The self as a multiplicity and a primer on Deleuze

1/3 Hall of Mirrors: Digital personae and the fractured dividual

We live online. We work, shop, socialize, date, and entertain ourselves on the Internet. It’s almost comical how reliant we are on our devices - obsidian oracles, techno-umbilical cords connecting us to the matrix. In many ways, our digital lives have become primary.

This series will apply the thinking of Deleuze and McLuhan to make sense of the increasing weirdness of our electrified existence. We’ll explore how the internet is changing our notion(s) of self and identity.

This first piece is a primer on key Deleuzian concepts with an exploration of the self as a multiplicity. We’re going to need these concepts and ways of thinking later on.

Thinking like Gilles: Difference and Multiplicity

"One day, perhaps, this century will be called Deleuzian." - Michael Foucault

So what has Deleuze got to do with this? The canon of Western philosophy (from Plato to Kant) grounds our thinking in stability, solidity, and separateness. The notion of an individual, a separate self, is connected to this line of thinking.

Contrarily, Deleuze offers a perspective that sees the world as ever-changing, in flux. It focuses on difference rather than identity. As technology accelerates change, his perspective becomes more relevant than ever. Thinking of the self as a multiplicity instead of as a unified whole resolves apparent contradictions and leads to interesting conclusions.

At the core of Deleuzian philosophy is the notion of difference, as formulated in Difference and Repetition. Reality fundamentally consists of different flows, moving at different speeds and interacting with one another. Everything is always in the process of becoming - there are no fixed points, separate objects, or terminal conditions. Our static concepts are just the crutches we need to navigate this changing world. The map is not the territory.

Any concept, from the notion of freedom to a grain of sand, is a repetition. This line of thinking harmonizes with the current neuro-scientific paradigm of predictive processing, where the brain is simulating a model of reality allowing humans to predict what may happen next. In reality, no two grains of sand are the same (e.g. when inspected with a microscope). However, each grain of sand is perceived as a repetition of the same concept, a “thing”. We form these concepts through their difference from other concepts.

Concepts, from this point of view, are not fixed platonic forms but are repetitions constructed from a field of pure difference. The universe, material flows, bodies, concepts, etc. are all moving and interrelating, repeating but bringing in new differences with each repetition. More of the same, but slightly different with each iteration.

Imagine a living neural tissue constantly making new connections while letting others atrophy. There is no essence of “red” to be found in the brain as a fixed entity. Rather, “red” emerges from a complex web of repetitions - concepts, memories, and associations, that are distributed in the brain and constantly updating. The same goes for all concepts. The idea of “multiplicity” captures this dynamic view. Multiplicities are made up of multiple, interconnected, and constantly changing elements. Without a fixed center or clear boundaries, in constant flux.

These Deleuzian ideas aim to shift our ground for thinking from one of stability, unity, and essence to continuous change and difference. We move from a clean cartesian grid filled with platonic forms to a messy, organic system of pure potentiality.

Reality is a piece of music. But it’s not playing Mozart, more like Arnold Schönberg meets Brian Eno.

The self as a multiplicity or why wholeness is passé

I am large, I contain multitudes. - Walt Whitman

Let’s apply this to the notion of the self. The common intuition of the self as a personal unchanging essence inevitably leads to confusion. From the cellular ship of Theseus to the experiential fact that we are very different people by ourselves, on a night out partying, or at dinner with our parents - there are innumerable contradictions created by this view. “Self” simply has different meanings in different contexts, and in fact consists of different elements. Acknowledging that resolves all of these philosophical problems at once.

“Self” means at once

the social convention of personhood (used in social relations),

a center of narrative gravity (including memories),

a unique perspective on the world (including consciousness and perception),

or a biological body-mind (including sensations and agency).

Depending on the context, what is meant by the self is any of the elements above or a combination of them. On top of that, each of these elements is constantly evolving, and none of them is really persistent over time. Each of them is a repetition, in Deleuze-speak, from a personal story to identification with the body as “me".

The process of identification is what stitches together these different repetitions into a self that appears unified and consistent over time. Identification is the act of putting an element that we think is ourselves into the perceived center of experience: My relationships, my story, my perspective, my body. This happens mostly unconsciously. Without examination, it makes sense that all of this is simply “me”. A bit of scrutiny reveals quickly what Buddhists have been preaching for centuries (under the term “Anata” = non-self): there is no unified persistent self. Rather, the self consists of different elements that are all constantly changing and interacting.

The self is multidimensional

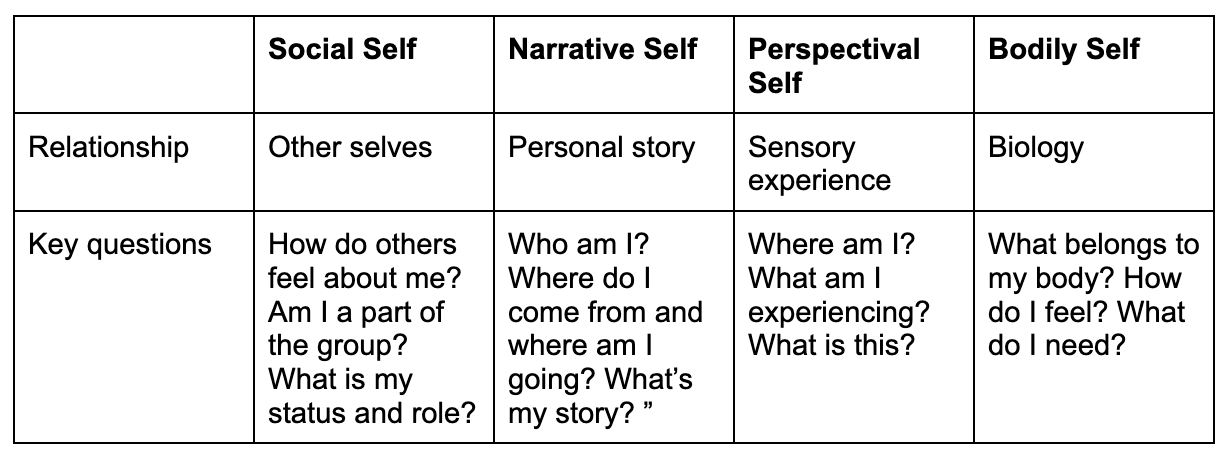

These different elements of self stretch across four different dimensions, outlined in the table below.

Viewing the self as multiplicity reminds us that those dimensions are always interdependent and in flux, and can never provide an exhaustive description. Don’t buy into the neat little table, the dimensions can’t ever really be separated.

Here is an example of the many ways they are interconnected: A bodily self who changes into a more upright posture will instantly have a more energized perspective, leading to more confident stories, which enables more assertive social interaction. The interactions between dimensions of self happen dynamically and in all directions. The self is a multiplicity.

Psychotherapy knew all along that self is a multiplicity

Starting as far back as good ol’ Sigmund, the self is not viewed as a unified whole in psychotherapy, but rather as multiple interacting parts (e.g. id, ego, superego). Internal Family Systems (IFS) takes this a step further. In that framework, there are numerous semi-independent parts. Parts are often “split off” by past traumas and have complex relationships with one another (e.g. “protector parts” vs. “exiled parts”).

Different parts relate differently and have different stories and different perspectives. Each “self” was really just a part of the self, a repetition of some elements. There was never a fixed self in the first place. Rather, the self is a fractal tapestry of relationship, a multiplicity.

Taking this frame seriously has important implications for what it means to be psychologically healthy: Rather than striving for stable integration, the goal becomes harmonious, adaptive differentiation. Allowing different elements of the self to come up as required by any given situation. We’ll dive more into this in forthcoming articles.

This concludes our initial mise-en-place, and if you are still reading, you’ll like what’s being cooked next: First, we add a pinch of McLuhan into the mix. We then stew over how the internet splits off dimensions of the self. Finally, we season with an exploration of how different parts align themselves with different personae across platforms to conclude the second course of the series.