Why You Are Probably Working for the Devil

A Post-Metaphysical Grimoire (1/4)

The Devil has been in decline since the Enlightenment. Rationalist critique dismissed him as naive superstition, an inverse Santa bullying the foolish into compliance with outdated traditions. What survived was literary: the sexy anti-hero of Paradise Lost, an ironic metaphor for human corruption. At best, the Devil became psychological, that inner voice tempting you to eat the extra cookie.

“The Devil’s finest ruse is to persuade you that he doesn’t exist.” - Baudelaire

But evil didn’t retire when we stopped believing in its personification. The excesses of human cruelty - torture, genocide, existential risk - demand explanation. Yet among both the return to Christianity and attempts at updating traditional religions, the Prince of Darkness gets surprisingly little airtime. The Devil has been allowed to hide in the shadows for too long.

Evil is Real

I should confess something: I’ve had a crush on the Devil since I was a teenager, drunk on Nietzsche and the smell of my own potential. Oh, how I wanted to be that Übermensch, a joyous comet blazing a trail of hedonism through a meaningless cosmos. The devil wasn’t evil but a Promethean liberator who promised I could invent my own values. It didn’t hold.

No amount of rationalization could scrub away that foul feeling after an action I knew deep down was wrong. At first, I dismissed it as internalized social expectations, something to break free of. Then I tried the cosmic view: zoom out far enough, and everything is predetermined, serial killers are just generational trauma with legs. And isn’t the bad necessary for the good anyway? Yin requires yang. The Devil as God’s left hand.

None of it worked. The feeling didn’t track social norms, and it didn’t dissolve into determinism either. Some accepted things felt deeply wrong. Some frowned-upon things didn’t trigger it at all. It felt like perception, like recognizing something about the situation itself (not projecting onto it). My moral compass was picking up signal, which means my teenage Luciferianism had a problem. I now believe that good, bad, and evil exist independent of my ideas about them. But here’s what took longer to see:

Evil is not just “very bad.” Evil breaks the moral frame.

That’s why murder feels qualitatively different from theft: It annihilates all possibility of future good for someone. So what counts as evil? Depends on who you ask.

Three Definitions of Evil

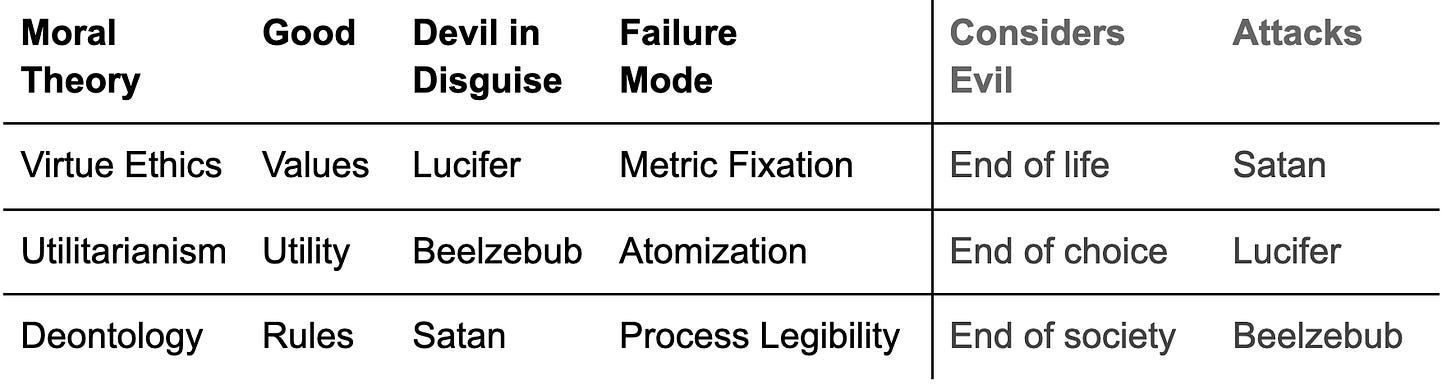

Moral philosophy has been stuck in a three-way stalemate for millennia. Which tells us that the answer is probably “all of the above”, each capturing something real. Each draws the line between bad and evil in a different place.

Virtue ethics grounds the good in the capacity to act according to your values, character, and principles. We can’t know the consequences of our actions, so what matters is showing up right: brave, honest, paying attention. Unfortunately, “I meant well” is the most common excuse at every war crimes tribunal. And yet there’s something here. It is clearly bad to act from a place of cruelty and selfishness. Evil, however, is what threatens the very foundation of all values: life itself.

Evil is the end of conscious life, the last light going out.

Utilitarianism is focused on the consequences of actions. Actions are good if they lead to well-being (“utility”), and bad if they lead to suffering. If we could calculate the total impact of our actions, we’d know what to do. Unfortunately, the hardware running that computation (us) struggles to remember a phone number. More importantly, humans are surprisingly different; my utility function is distinct from yours. The ability to choose is at the very foundation of the utilitarian good. Actions whose consequences result in negative utility are bad.

Evil is darker: destroying the capacity to choose at all.

Deontology is the ethics of rules. Since we can’t calculate consequences and good intentions routinely backfire, we need heuristics. Don’t lie, don’t steal, don’t kill. These norms are load-bearing. The problem is that rules work until they don’t, and then they keep working anyway. But get rid of too many rules, and there’s no society left. Breaking a rule is bad.

Destroying the game itself is evil.

Three frameworks, three definitions of good and evil. As we’ve noted above, all of the moral theories hold an important truth. If one of them ignores the other two, it becomes a devil in disguise. A good pushed past its breaking points becomes a force for evil.

Lucifer: The Light That Blinds

Lucifer translates to “Light Bearer”. Like Icarus, he flew too close to the sun. Intelligence, ambition, and impatience fused so intensely that he was banished to hell for his arrogance. He’s been headhunting ever since.

He disguises himself as a liberator, fighting against unjust tyranny and seeking to overcome all limitations to human potential. The Luciferian promise: if we just know enough, we can fix everything. Poverty, disease, loneliness, and death itself are all merely engineering problems awaiting sufficient data. Our intelligence raises us above the crude patterns of evolution and nature. We must transcend our stinking flesh.

He whispers into the ears of every techno-utopian and transhumanist. His priests speak of “frictionless” experiences, of problems “solved at scale.” Conquering the universe and racing towards the singularity are Luciferian endeavours. Lucifer doesn’t want to become God. He wants to build God, and in doing so, prove that God was only ever a dumb machine.

You know Lucifer has taken residence when you begin measuring your brain waves during meditation. Or tracking Happiness KPI’s in a Notion doc. Lucifer invented hustle porn: Count your steps and your calories, track your sleep. His trick is not denying the sacred but explaining it away. Love becomes attachment theory, and awe becomes predictable neurochemistry.

Lucifer is the corruption of virtue ethics. Instead of providing a field of value generated by the tension of competing virtues, he applies optimization logic to it. The choosing self becomes a metric-maximizing machine.

By optimising a single metric, you are blind to everything else.

Beelzebub: The Rotting Swarm

Beelzebub means “Lord of the Flies”. While he isn’t as famous as his two brothers, he is probably the most dangerous devil of our times. Beelzebub doesn’t command the flies; he is the swarm. That buzzing haze of small hungers, none significant enough to resist, all of them together enough to strip a carcass clean. His domain is rot, but not the dramatic rot of plague or apocalypse. The quiet kind. The kind you don’t notice until you realize you’ve been scrolling for three hours and can’t remember why you picked up your phone. Beelzebub is why you’ve opened the fridge four times in an hour without being hungry.

Beelzebub arrives wearing the mask of the emancipator. He speaks of freedom, choice, and personal agency. But his liberation is a trap. He maximizes personal preference until it becomes meaningless among a thousand options that don’t matter - junk food, porn, and doomscrolling. The more you can do whatever you want, the less “you” remains to want anything, the more you act like the rest of the swarm. Freedom without structure isn’t freedom, but diffusion. Beelzebub invented notifications, variable reward schedules, and infinite scroll feeds with autoplay. Beelzebub is the devil of hyperbolic discounting.

His trick is not lying but bullshit, diffusing attention while totally indifferent to truth. He doesn’t argue or convince; he merely makes other things salient. Were you going to work on something meaningful? Here’s a thirst trap, and your friend just posted this meme. Buzzing, demanding attention, because attention is all he eats. The inner swarm manifests as impulse unchained from intention, the accumulation of micro-surrenders slowly rotting attention spans. The result: You have access to all human knowledge, yet you find yourself watching a 12-second video of a hydraulic press crushing a rubber duck.

Utilitarianism taken to the extreme collapses utility into immediate gratification. Beelzebub eats away at your temporal horizon until the self dissolves into the swarm.

The devil doesn’t need your soul if he has your attention.

Satan: The Weight that Crushes

Satan is the force that makes rebellion necessary, restriction calcified into cruelty. The tyrant presses downward, and everything beneath him turns to stone. “Satan” is associated with Saturn, the planet of restriction, time, and law. The rigid and cruel laws of death and time. Satan builds systems so perfectly legible that the illegible mess of actual living falls through every crack. The process becomes more real than people.

He disguises himself as a protector from chaos and promises to purify what’s unnatural. He wants to preserve cosmic order by eliminating whatever threatens it: the degenerate, the immigrant, the deviant. Satan prosecutes whoever fails to conform. The fundamentalist burns the heretic to save doctrine. The bureaucrat lets refugees drown because their paperwork is incomplete. The algorithm denies medicine because the diagnosis code doesn’t match. Satan is the devil of the spreadsheet. He is the government form that asks for your mother’s maiden name, your tax ID, and a utility bill - then rejects the upload because the file is 3 KB too large. He’s the hold music you’ve memorized. The calendar invite for a sync to prepare for the pre-meeting.

But Satan also colonizes the inside. Not as the dramatic inner critic who calls you worthless (that’s too obvious). The subtler voice that says you should have replied to that email already. That you’re behind. That other people your age have figured this out by now. He makes you feel slightly, persistently inadequate. That’s enough to keep you compliant. He is the weight of every “should” that has nothing to do with flourishing, every rule that serves only its own perpetuation.

Even more fundamentally, Satan is the tyranny of the propositional, the left hemisphere’s coup d’état against the rest of knowing. Under his influence, only that which can be articulated counts as real. What cannot be formalized cannot be seen. When deontology is taken too far, it gives rise to tyranny.

I always knew bureaucracy was Satan. Now I know why.

A Systems View of the Devil

Three faces of evil. But why faces at all? Why personify? Since Scott Alexander’s Meditations on Moloch, it has become more common in certain corners of the internet to use the concept of egregores, entities that emerge from group behavior with quasi-agency and alien goals. A corporation isn’t just a contract between people; it uses people as fuel, often against their interests. It wants to expand bureaucracy (not efficiency) and maximize profit. Causality flows downward from systemic incentives to individual behavior (a CEO who gets too impact-oriented will be replaced).

Why use the egregore frame? First, it helps us see how structures can “want” things that no individual inside them wants. A corporation optimizes for profit even when every employee would prefer it didn’t. The system has desires. That’s strange and important.

But there’s a deeper reason. Evil at scale is hard to perceive. It’s like climate change, too distributed in time and space for our brains to grab. We evolved to detect agents, not gradients. Giving the system a face, a name, even a personality, is compression that actually helps. Egregores are a UI for hyperobjects.

And it redirects blame. When a system fails (a financial crisis or a slowly boiling planet) we hunt for a villain. But often there isn’t one. Everyone was following the rules, maximizing local metrics, and behaving rationally within their scope. The structure was the villain. Egregores let us stop witch-hunting individuals and start exorcising the incentives that summoned the demon.

Moloch is one such demon. But I’m arguing there’s a deeper layer that produces them. There are generator functions of demonic egregores, three systemic drivers that combine to summon these entities. And we’ve already met their faces.

The Stuff Demons are made of

Moloch, Mammon, and other demonic egregores are all created from the same material. This is where the notion of a post-metaphysical Devil makes sense. The Devil is the generator function of misaligned egregores. Each moral theory, when pushed into its failure mode, becomes one of three systemic drivers: Metric Fixation (the will), Atomization Paradox (the fuel), and Process Legibility (the nervous system).

You’ll recognize these as the domains of our three faces of the Devil. Every egregore requires all three drivers to function. What differs is which one leads. A Luciferian egregore is metric-dominant, a raging mob is at the centre of a Beelzebubian one, and a Satanic egregore revolves around process. The other two are always present, just subordinate. Think of it as demonic DNA: same three base pairs, different expressions.

Metric Fixation is the dynamic described as Goodhart’s Law or Value Fragility. A single metric (think profit or GDP) is maximized while everything else is ignored. If you tell a corporation to “maximize shareholder value”, it will treat poisoning the local river as a clever efficiency hack. The North Star Metric is the will of the demon, and it does not care about your externalities. This is the Luciferian ascend, obsessively climbing whatever hill has been specified.

The Atomization Paradox is what provides the fuel. Egregores run on humans. The best hosts don’t have anything other than Late Capitalism OS running. If they are bound by deep loyalties (such as religion, family, or culture), they might not mindlessly follow the incentive gradients laid out for them. The best fuel is atomized humans, only bound to their own self-interest. Fungible, neutral building blocks. “Free individuals” who must “find their own truth” don’t have an immune system. The Result: A paradox where everyone is obsessed with “being unique,” yet everyone acts the same. An atomized population is like loose sand, easy for a demonic egregore to mold into bricks. This is Beelzebub’s feeding ground.

Process Legibility is the driver behind mindless bureaucracy, the curse of high modernism. It is the drive to turn everything into a repeatable, legible, and “objective” process. James C. Scott has documented in “Seeing Like a State” how complexity is reduced until measurable units are made legible to a bureaucracy. A forest is complex, but timber is measurable. Biodiversity is messy, CO2 is legible. This process acts like the nervous system for the egregore. If the friction of human judgment can be replaced by automated processes, the egregore starts waking up. This is Satan’s architecture.

These three drivers are the anatomy of a demon. They combine like this: the atomized population removes resistance. The metric provides direction. The legible process removes friction. The system self-organizes into a predator, and the people inside it can’t see what they’re part of. They’re just following the incentives, making locally rational choices, doing their jobs. The loop closes. The egregore wakes up.

These devils have been with us at least since the dawn of agriculture. But they are particularly vicious in our times of hyper-financialized modernity.

The Hidden Face and the Scapegoat

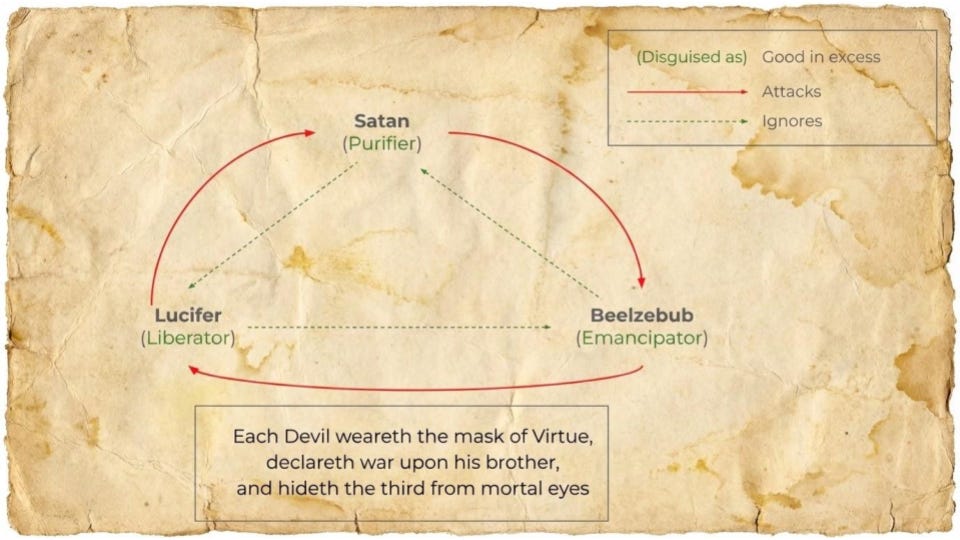

Now the con gets interesting. Each devil doesn’t just hide behind a good, but also attacks another one as a distraction. From the internal logic of a moral theory, its hidden devil genuinely seems like the good guy. Not even cartoon villains think they are serving evil; they’re locked in on what they consider good. However, from the perspective of that good, another one of the devils comes into focus as evil and is attacked vehemently.

Virtue ethics (where Lucifer hides) grounds the good in choice in accordance with values. From its vantage point, Satan is the source of evil that must be defeated because he threatens life itself, the foundation of all values. None of the virtues we care about are worth anything in an empty cosmos. Satan’s cruel processes of death and decay must be vanquished. Not just the unforgiving rules of nature, but bureaucratic systems so rigid that life itself can’t squeeze through the cracks. Entropy wins by procedure and needs to be stopped. We need to liberate ourselves from tyranny.

Utilitarianism (where Beelzebub hides) cares about utility. Preferences differ, so the ability to choose sits at the foundation. Lucifer is a threat to personal choice because he has collapsed the good into a single metric. When everything becomes optimised, the capacity to choose according to your own values disappears. Once you’ve picked your metric, there is no longer a choice to be made; there is only the math of the next step. You stop being a moral agent and become a fleshy calculator. Humans need to be emancipated from technological control.

From the perspective of deontology (where Satan hides), rules are good since they allow society to function. Chaos is the enemy: crumbling social norms and atomized individuals. When everyone is scattered into pure individual choice, unbound by a shared reality, there’s no society left to have rules in. Beelzebub must be stopped, lest the swarm consumes the polis.

Beelzebub appears to be empowering individual choice. Lucifer pretends to be liberating us from unjust tyranny. Satan poses as purifying chaos and restoring order. Each devil disguises itself as the good from one moral framework while attacking another devil who threatens the basis for that good.

The Devil’s Oldest Trick

Here’s where it gets nasty: There is another layer of the ruse. The scapegoating wasn’t just a distraction from the devil in disguise, but also a cover for the third face of the devil to sweep in for the kill. Here is how it looks from each perspective:

The tech rationalist (Lucifer as liberator) sees Satanic restriction everywhere. Dumb laws, slow FDA approvals, the arbitrary limits of biology. He is going to disrupt all of that. But he is so locked onto the Luciferian good (intelligence, optimization, scale) that he doesn’t feel the Beelzebubian rot setting in. He wants to upload his consciousness, but right now he is drinking beige nutrient slurry over the sink because chewing is an inefficiency. He optimizes his sleep architecture to the millisecond but wakes up in a windowless “pod” that smells like stale air and unwashed polyester. He attacks the limits of nature, while Beelzebub quietly dissolves his muscle mass and his ability to hold eye contact.

Conversely, the liberationist (Beelzebub as emancipator) sees Luciferian control everywhere. Old white men who think they know better, technocrats reducing life to metrics. She wants to free everyone from the tyranny of measurement. Resist the quantified life. But she is so locked onto her version of the good (choice, fluidity, personal sovereignty) that she doesn’t notice structurelessness turning into tyranny. Every norm she deconstructs forces her to negotiate reality from scratch. While she may have escaped the oppression of patriarchy, the crushing bureaucracy of scheduling software and 4-hour processing talks snuck up on her. Attacking Lucifer wearing Beelzebub’s face turns out to lead to a stealth siege from Satan.

Finally, the traditionalist (Satan as purifier) sees Beelzebubian rot everywhere. Crumbling communities, a culture drowning in meaningless choice. He demands Law and Order. Retvrn. But in a complex world, total order requires total surveillance. To ensure the border is secure, he builds a biometric dragnet. To ensure crime is punished, he installs facial recognition on every corner. He attacks Beelzebub with Satan’s walls, not realizing he just laid the fiber-optic cables for Lucifer’s panopticon. Satan flattens human life into a “pass/fail” binary and Lucifer helpfully offers to automate the grading.

The Devil’s oldest trick is to vehemently oppose one form of evil while wearing a second face and ignoring the third. Exalt one, attack another, ignore what’s in your blind spot. Each faction is convinced they’re fighting the good fight. Each one serving a devil they can’t see because they’re too busy battling a devil they can. This maps, interestingly, to the three Buddhist poisons: craving, aversion, and ignorance. You crave your devil’s promise, rage against your devil’s enemy, and stay blind to the third. The wheel keeps turning.

The way out is to refuse the false trilemma. We need all three notions of the good at once: the capacity for choice, the flourishing of conscious life, and the social fabric that holds us together. Any one of them maximized at the expense of the others is no longer good, but a devil in disguise. I started this essay thinking the Devil was underrated. I was wrong about why. The Devil isn’t underrated because we’ve forgotten about evil. He’s underrated because we don’t recognize him when he’s wearing the face of our favorite good. I worshipped optimization and despised arbitrary constraints. What I didn’t notice was Beelzebub eating my attention from the inside. The rebellion against structure left me rotting in a swarm of distractions I mistook for freedom. What broke the spell wasn’t more liberation. It was binding the devil with some good old discipline. I had to build a protective circle that keeps the swarm out. The Devil’s trick only works if you think there’s one devil. There are three, and the one you’re not watching is the one that gets you.

Wake up friends, new meditations on Moloch just dropped!

This is so so good thank you

I love the idea of applying the trinity/trimurti to evil, but I’m still struggling a bit to identify a clean correspondence between the trinity of evil and the (Father-Son-Spirit)/(synthesis, thesis, antithesis)/(create, preserve, destroy). Maybe it relates to the old saying “die young or live long enough to become a villain”. That is, maybe a Father that lives too long becomes Satan, the Son becomes Beezelbub, the Spirit becomes Lucifer—so Evil is like a transition— an edge between nodes of good.