This piece was co-composted with Andy Tudhope

The most powerful secrets used to be imparted in confessional booths, under holy oath. The most vulnerable hopes and doubts were once whispered between lovers, held in intimate trust. We've replaced the confession booth with the chat box. Same vulnerability, different priest: this one never forgets and has no vows to break.

It may seem like the issue of privacy is just a simple trade-off between freedom and safety, between self-expression and convenience. And why wouldn’t we choose safety and convenience? It can seem like we have bigger problems than chasing some outdated ideal that only hardcore libertarians and criminals care about.

Privacy is much more foundational than it seems at first glance. Privacy is to the social sphere what property rights are to economics, its very foundation. We’ll see how privacy defined as the right to selective disclosure enables freedom and intimacy. Privacy is intimately connected to personhood, power, and information itself.

Privacy is a membrane.

It determines what stays protected and what we choose to reveal. Scratch the surface of this trite trade-off and discover the informational architecture of human flourishing.

Beyond the Trade-Off: Privacy and Personhood

Thinking of privacy as a trade-off is an intuitive starting point. The classic framing pits individual freedom against collective security. Privacy seems like a dial to turn between these two competing values. Give up some personal autonomy, gain protection from terrorism, crime, and fraud. If surveillance keeps us safe, why not accept it? After all, a good person has nothing to hide, right?

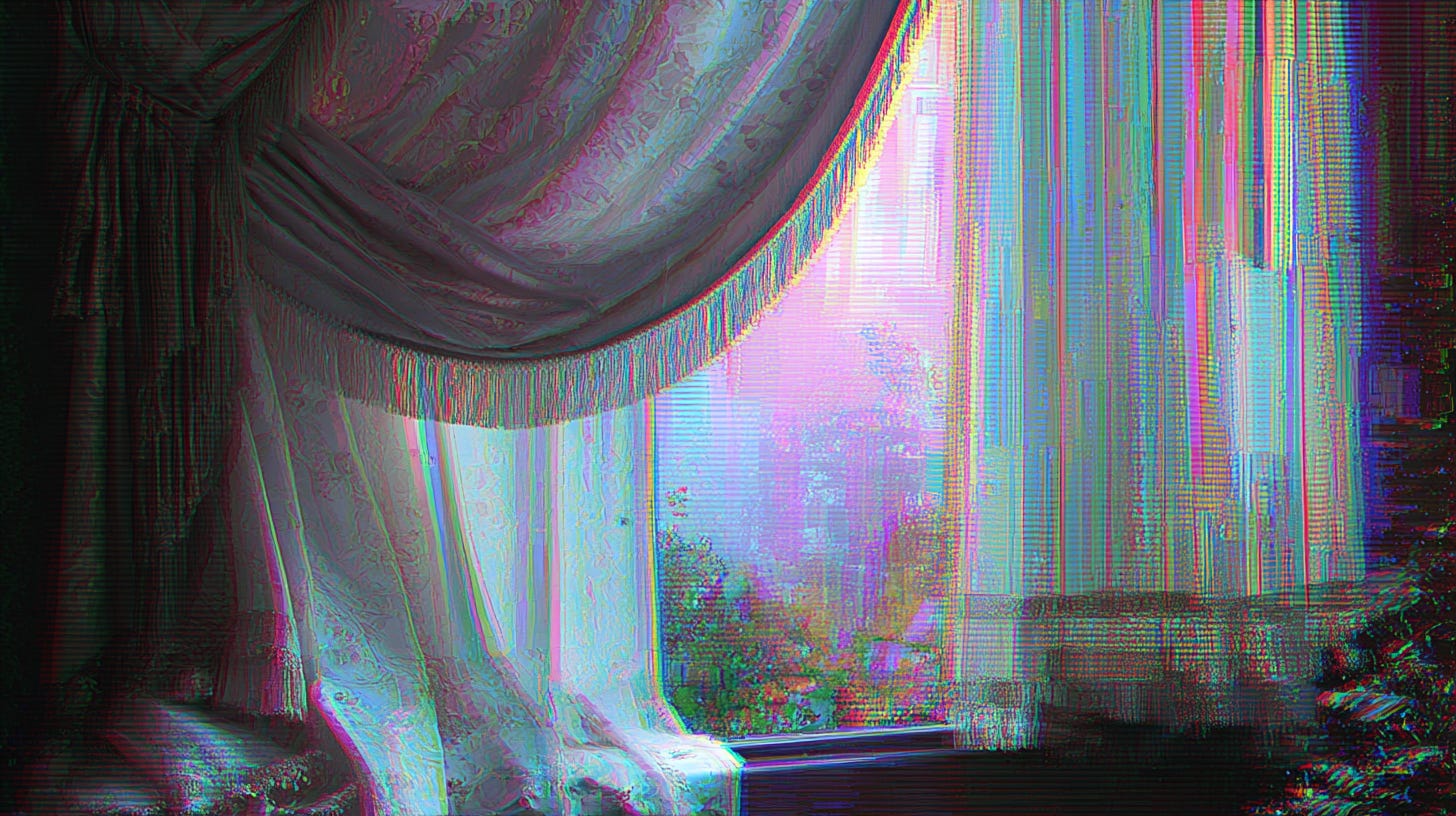

But this trade-off misses the deeper causation at work: privacy isn’t just a form of freedom, but it creates the very conditions for it. Where do you feel the most free? Probably not on a wide open field, but in your home. It’s not just because you’ve designed this personal space, it’s because your windows have curtains, and your room has a door, even a lock. Windows, curtains, and doors are all different membranes that modulate what passes through. Freedom lies in choosing to open your door to somebody or to put yourself out there. To be able to open it, you need the door at the outset. These membranes don't just separate; they create space where you can be yourself and try on different identities without judgment. Pseudonymous accounts work the same way: masks can reveal, not just hide.

Here's where it gets deeper. This capacity for freedom rests on something more fundamental: personhood itself. Jeffrey Reiman argued that privacy barriers allow infants to develop into persons by learning they have exclusive rights over their bodies and minds. Without this boundary between self and world, there's nobody to be free in the first place. That’s why privacy is a human right: Without it, we don’t just lose freedom but undermine the very foundation for it.

The cocoon of privacy is what allows us to become.

The moment we think we're being watched, this freedom to become evaporates. We internalize the observer's presumed judgments and self-censor. Bentham designed the Panopticon around this principle. Today, we carry that universal peephole in our pockets. Before we turn to the implications of our pocket panopticons, we need to clarify our understanding of privacy as a membrane.

Selective Disclosure and Information Gradients

The Cypherpunk Manifesto states that, “Privacy is the power to selectively reveal oneself to the world.” We've seen that selective disclosure, as the membrane between self and world, is the basis for personhood. Rather than simply withholding information, this definition emphasizes both protecting and revealing: what is revealed to whom in what context.

What makes some information feel more private than others? Think about it: when someone asks 'How are you?' and you say 'Fine,' you've shared nothing meaningful. But if you answer, 'Actually, I'm thinking of leaving my job,' the conversation suddenly takes on weight. Claude Shannon figured out why:

Information content is inversely related to probability.

The more improbable the message, the more information it carries. Pineapple.

Once you see information this way, the membrane-logic of privacy snaps into focus. Our public personas are deliberately predictable: low information content that maintains smooth social functioning. The information we guard most carefully breaks this predictability: our deepest fears, our passwords, our contradictions. This high-information content is exactly what creates both intimacy (when shared voluntarily) and vulnerability (when exposed involuntarily). This is why oversharing on social media undermines intimacy by flattening disclosure and becoming predictable. It’s also why you should use random passwords.

Privacy creates information gradients in relationships. Concentric circles of membranes where the most trusted connections access the highest information content. But here's the key: The same secret creates intimacy when disclosed voluntarily to a lover, but becomes a weapon when extracted by manipulation.

Privacy is the membrane that ensures information flows by choice, not force.

This is why privacy is foundational for both intimacy and power. When we control what information crosses our boundaries, we maintain agency over our relationships and our lives. But when that control is compromised, when our boundaries are breached, we become vulnerable to those who would use our secrets against us. Which brings us to the darker side of information gradients: how knowledge becomes power, and how privacy serves as our primary defense against its abuse.

Privacy and Power

Client confidentiality rules (e.g., for doctors, lawyers, and therapists) exist because your secrets can become someone else's leverage. Information that could embarrass you becomes blackmail material. Bonnitta Roy’s pithy definition of power is “who gets to move whom”. The power dimension of personal information explains why privacy violations feel so threatening.

In the digital age, this interpersonal dynamic has scaled to institutional proportions. The classical privacy-security trade-off asks us to surrender sensitive information to institutions tasked with protecting the collective, such as governments, tech giants, and financial institutions. Not coincidentally, these are now the most powerful institutions on earth.

Concentrating this much information creates dangerous accumulations of power. Instagram knows you're about to break up before you do, and serves you ice cream ads accordingly. Massive databases become honeypots for hackers. While giving up our privacy might protect us from crime at the margin, it merely relocates power and risk to central institutions. Trading off privacy for security seems like a good deal in the short run, but it’s fragile in Nassim Taleb’s sense: reducing daily volatility while creating conditions for catastrophic failure. Privacy serves as our primary defense against institutional overreach, which is why cryptography advocates fought so hard in the 1990s to secure our right to strong encryption.

However, this hard-won defense has been quietly eroded by digital convenience. Google Maps works better with location tracking enabled. Social media algorithms improve with engagement. Unlike obvious privacy surrenders (tax forms, medical records, etc.), digital surveillance feels voluntary, even empowering. We post freely and share openly, convinced we're exercising autonomy.

The pocket panopticon succeeds precisely because it masquerades as freedom.

Its manipulative powers strike covertly: I don’t notice how social media ads push just the right buttons at the right time to get me to consume. It’s not obvious that I’m receiving scam calls because an airline company has breached my phone number. Algorithmic control is the most subtle form of power yet. As Byung-Chul Han observes, “we feel free, even as we are controlled like puppets on algorithmic strings."

Online, we don't trade freedom for security. Instead, we surrender freedom while believing we're exercising it.

AI chat interfaces represent the apex of this Faustian bargain. We tell ChatGPT things we wouldn't tell our therapist, and somehow think this is progress. The companies behind these systems now possess unprecedented psychological profiles of millions of users. Behold, for the AI knows your true name.

Privacy is the Basis for Intimacy

Knowledge is not just a vector for power; it forges intimacy. Consider how some users fell in love with ChatGPT. Presumably, they felt deeply seen and understood by an AI that has learned a great deal about them. The membrane between self and other becomes permeable through disclosure, and we grow attached to whatever peers through that opening.

Who would have thought that intimacy is about information architecture? Arthur Aron's famous 1997 study "36 Questions That Lead to Love" demonstrated that strangers could develop romantic feelings simply by answering increasingly personal questions together. The mechanism driving this is "self-disclosure reciprocity". As I make myself vulnerable by sharing secrets, and you reciprocate with your own revelations, we create intimacy through mutual risk.

Privacy enables this process by making disclosure meaningful. If everyone already knew everything about everyone else, self-revelation would lose its bonding power. But intimacy isn't built from mere facts: Knowing someone’s favourite color is cute, but shallow. True intimacy is created by glimpsing each other’s souls: the accumulated patterns of surprise that make someone irreducibly themselves. In Shannon's terms, the soul is the multiplicity of accumulated surprise. (Yes, I just defined the soul using information theory. Deal with it.) Here's where it gets interesting: once established, intimate relationships function like encrypted channels. Even if strangers overhear your words, they miss the deeper meaning encoded in your shared history. This is why inside jokes are so powerful, and why breakups feel like losing a language.

The soul is the multiplicity of accumulated surprise.

This pattern extends beyond romantic relationships. A private journal fosters intimacy with oneself, enabling self-knowledge through unguarded reflection. Religious traditions recognize this principle by revealing advanced teachings only after extensive preparation. Jews traditionally studied Kabbalah only after the age of 40, while Tibetan Buddhist lineages require extensive preliminary practices (ngöndrö). Some teachings can only take root when the student has developed sufficient intimacy with the tradition itself.

But these same dynamics that create intimacy can be weaponized. Pick-up artists leverage self-disclosure reciprocity to get laid. Endless personal sharing without substance breeds narcissism rather than self-knowledge. Oppressive religious systems have known for millennia that selectively dishing out teachings is not just a power move, but a great customer retention hack. If you need to get intimate with your guru to receive the secret teachings, something might be off. When intimacy becomes a transaction rather than a choice, the boundaries of selective disclosure are crossed.

The Tao of Privacy

Privacy follows nature's own logic. Just as membranes appear at every scale in biology, from cell walls to skin to the planetary atmosphere, selective disclosure governs information at every level of human experience. Even if we wanted total transparency, our communication channels couldn't handle it. Information has its own natural unfolding: this essay needs an introduction, chess requires learning openings first, and context determines what can be received and understood. You should inform your doctor about your hemorrhoids and your priest about your sinful thoughts, but not vice versa.

Maybe this is why Heraclitus observed that “Nature likes to hide.” It's not just about camouflage, though nature does love its disguises. The deeper insight is that revelation requires the right conditions. An acorn can't reveal itself as an oak tree all at once; it has to unfold step by step. Heidegger called this “unconcealment”: truth as a dance between showing and hiding.

This mirrors how selective disclosure works on the level of the self. There is no fixed authentic self that we choose to reveal or conceal. Rather, our authentic selfhood emerges through the very process of selective revelation. We become ourselves through choosing what to share with whom, when, and how. Like a fractal of membranes, this principle scales up through relationships, communities, and institutions.

So what do we do with this? How do we live as humans in a world designed for data extraction?

Start with information gradients. Your roommate doesn't need the same access to your psyche as your therapist. This isn't elitism, but basic emotional hygiene. Practice strategic invisibility. Use pseudonyms for experiments. Keep a journal no algorithm can read—pen and paper, like some kind of medieval monk. The capacity to disappear enables the freedom to become, which is why every totalitarian regime starts by making anonymity illegal. Most importantly, defend the architecture itself. Privacy isn't about hiding dirty secrets; it's about preserving the conditions where anything beautiful can emerge.

Just as property rights create the incentive structures that enable markets to function, privacy creates the information architecture that enables society to flourish. Privacy isn't about hiding your browser history. It's about preserving the space where souls can actually develop. In a world obsessed with transparency, opacity becomes the ultimate act of rebellion. Not against society, but for it. The confession booth knew something we've forgotten: the most sacred conversations happen behind closed doors.