Split the Ikigai

Why the Dream Job is a Failure Mode

The quest for the dream job is a particularly vicious mind virus that has been spreading for decades. The memeplex crosses Romanticism with Protestantism, captured by corporations.

Romantic individualism insists your life should be a unique self-expression, not the mere fulfillment of a social role. You are an artiste, and your work should reflect that singular inner flame. The Protestant work ethic, meanwhile, has always sanctified labor and morphed into holy self-actualization as the ideologies crossed.

Then came the capture: Corporations discovered that employees who see work as identity will tolerate longer hours, lower pay, and worse conditions, because quitting would be abandoning their calling. The Romantic supplies the yearning, the Protestant supplies the guilt, and the corporation collects the surplus. A perfect memetic honey trap: you get to feel like an artist while being exploited like a serf.

There is no Such Thing as a Dream Job

High expectations are the architects of misery, and the Ikigai provides the blueprint. You’re supposed to love your job. And on top of that, you must have impact. Your CSS tweaks should somehow address the world’s “deep hunger.” You must save the whales, monetize your passion, and hit your OKRs, all before lunch. Good luck.

It’s easy to mock, but my bite comes from personal frustration. I’ve wasted years chasing after the pot at the end of the rainbow too. I founded a startup I was excited about, only to find myself disconnected from our mission, three pivots later. Many times over, I’ve felt low-key guilty when I didn’t love my work, and also when I loved something and didn’t monetize it. That guilt, I now believe, was unwarranted. Neither you nor I are entitled to our fairytale dream job. Worse, chasing after it can pull you off the path toward a livable life.

The Contradictions of Love and Money

The “passion economy” demands that your economic function and your emotional satisfaction must align in the same activity. If you work for money, you are a sellout. If you pursue passion but can’t pay rent, you are a loser.

The problem is that economic and artistic activities have different structural incentives.

Economic activity is by definition work you do on behalf of somebody else. The priorities, scope, and timeline are set by your employer/client. It also means the activity is instrumental. You do it in order to get paid. In contrast, you would do what you love doing for the sake of the activity itself. You would pay to do it (as people do for hobbies), not demand to be paid.

If you try to monetize your hobby, you often destroy the joy by introducing external constraints and crowding out your motivation. I love scheming and taking risks. I would have been a dope assassin. Instead, I advise startups. Advising founders gives me joy, but packaging my advice into something billable often sucks the life out of it.

The fastest way to kill what you love is to try to get paid for it.

The market logic (differentiation, optimization, scale) will turn your joy into a side hustle.

Bad Targets

Even if monetizing your passion didn’t kill it, the Ikigai also sets bad targets with the other two circles.

We’re also supposed to be doing something that the “world needs”. What does the world need? And how would you know? The problem with impact-oriented thinking is a mismatch of scale: global challenges are illegible to individuals. You are not the protagonist of reality, sorry.

Finally, we’re also supposed to be “good at it”. But if you commit to an activity with attention and curiosity, you can’t help but improve. Talent is overrated, obsession is what drives success. Narrowing the search to activities you’re already good at prevents you from discovering the weird niches where you might eventually dominate.

The Ikigai demands four circles overlap. Two are in direct conflict, two are bad targets. Zero overlap. One nervous breakdown.

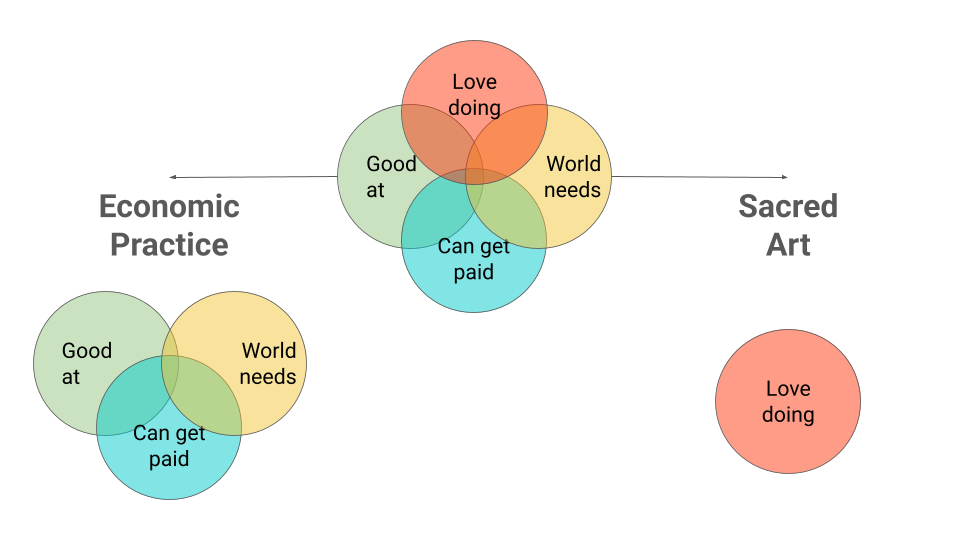

Split the Ikigai

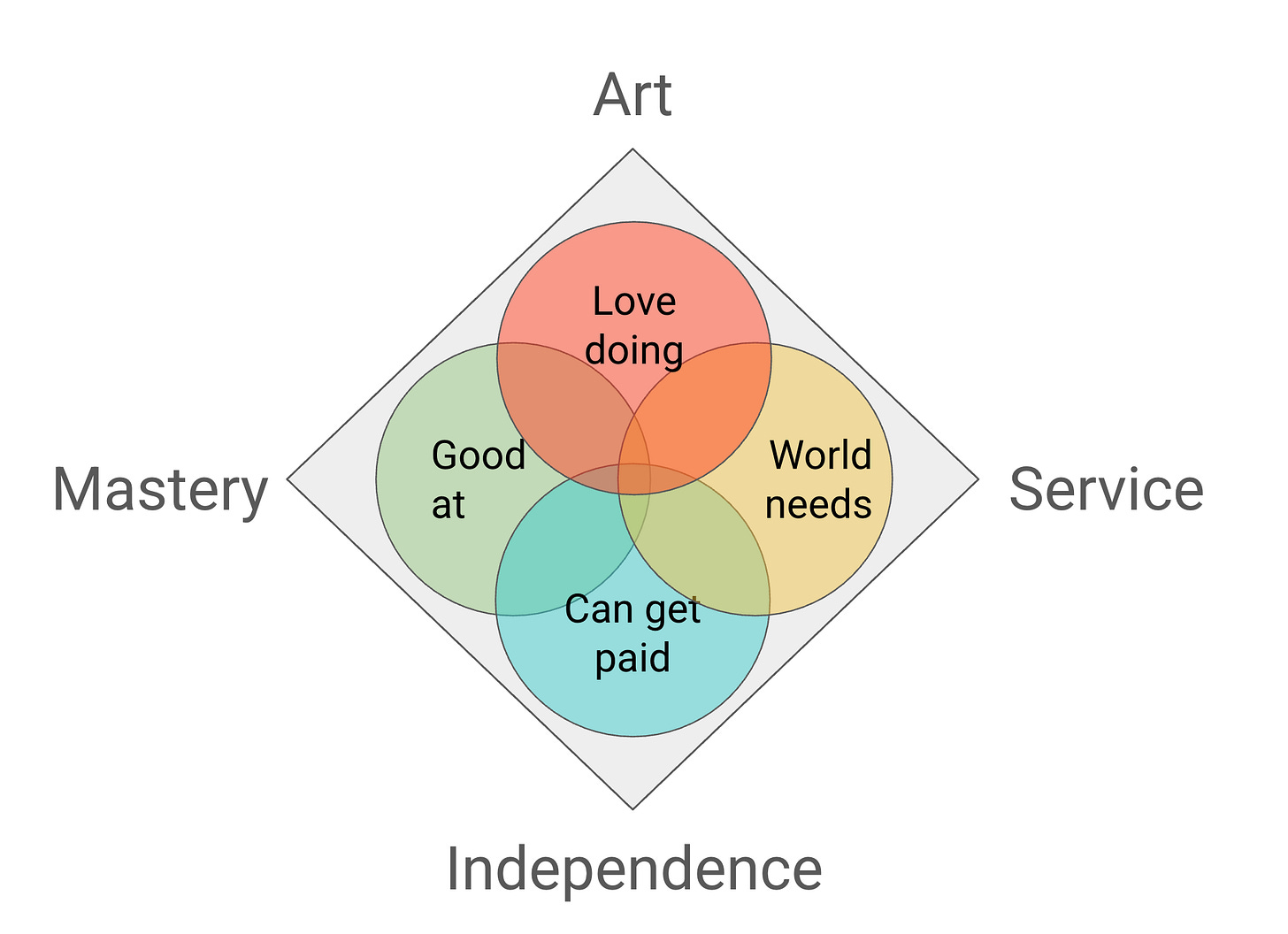

The Ikigai persists because it contains partial truths. The four areas are relevant landmarks: Art, Service, Independence, and Mastery.

Maximising for one (usually finances) leads to unhappiness. Even neglecting one is unsatisfying. It sucks to hate your job. It sucks to lack meaning. It sucks to be poor. And finally, it sucks to suck.

The mistake is to assume they must converge in a single job. They don’t. We can solve for them sequentially or in parallel, but rarely simultaneously.

Back to the Future

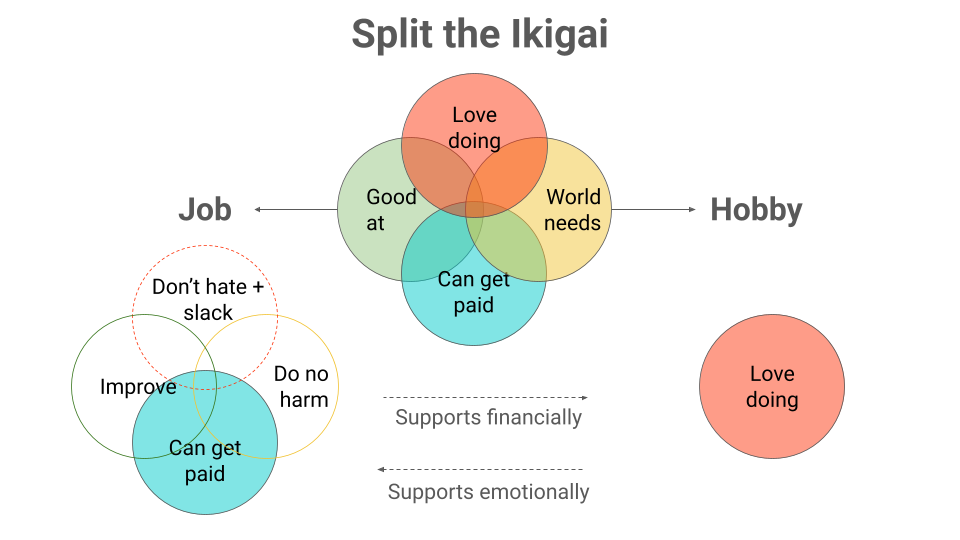

If you’re young, you probably should get a job. And here comes the contrarian take: You should get a hobby too.

A job and a hobby.

There is a reason this worked for your parents. Keeping a membrane between work and play makes them mutually supportive: The job generates the resources to subsidize the art. The art restores the energy required to endure the job.

This isn’t a retro fantasy about larping the 1950s. That world is gone. We need a modern architecture to unite these pillars.

Economic Practice

Yes, get a job, but not just any job. While demands of the original Ikigai are unrealistic, we can still use the framework for useful constraints.

Instead of enforcing that we love our job, we should just make sure that we’ll still have some time and energy left to do what we love. All else being equal, choose the 9 to 5 job that pays less over the high-earning 996. Treat the job as a subsidy for your existence. You are maximizing for slack (time/energy), not just currency.

Another useful constraint is the rate of skill acquisition. As long as you are getting better over time, the “good at” portion of the Ikigai will take care of itself.

Finally, don’t do anything obviously harmful to your customers or the world. If we can get paid without doing any harm, there is a good chance the world needs what we’re doing. Over time, we can hit three-quarters of the Ikigai.

While we narrowed the search space with these constraints, we still have far more options than Ikigai-hunters. And we’ll need them. While good corporate jobs are scarce, the internet offers a long tail of opportunity. Entry costs are near zero.

You can vibe-code an app, monetize a hyper-niche obsession, or sell MP3s to reprogram attachment styles. It’s no coincidence half your digital nomad friends are suddenly life coaches. The category of “can get paid for” is vastly larger than the category of HR-approved roles. I know people paying rent as ritual consultants, attention co-pilots, and lore architects.

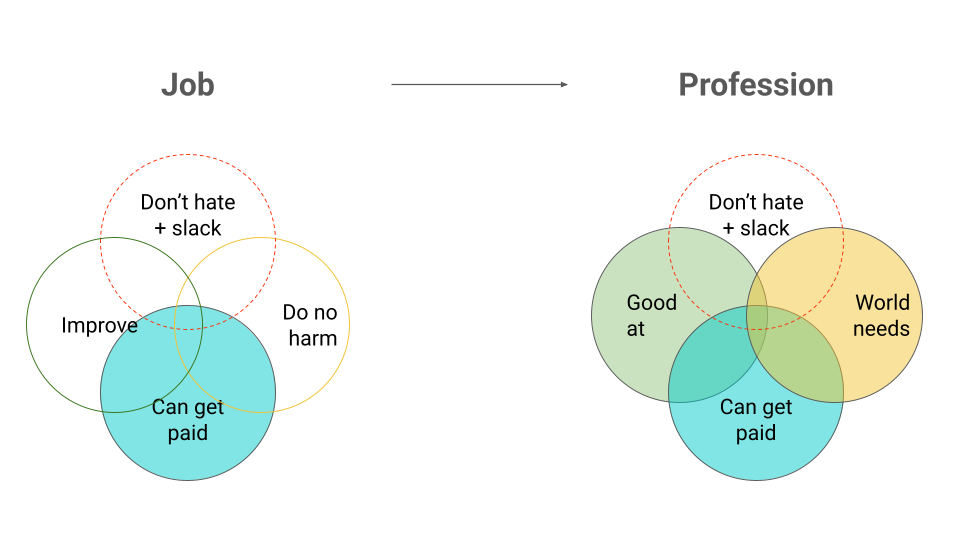

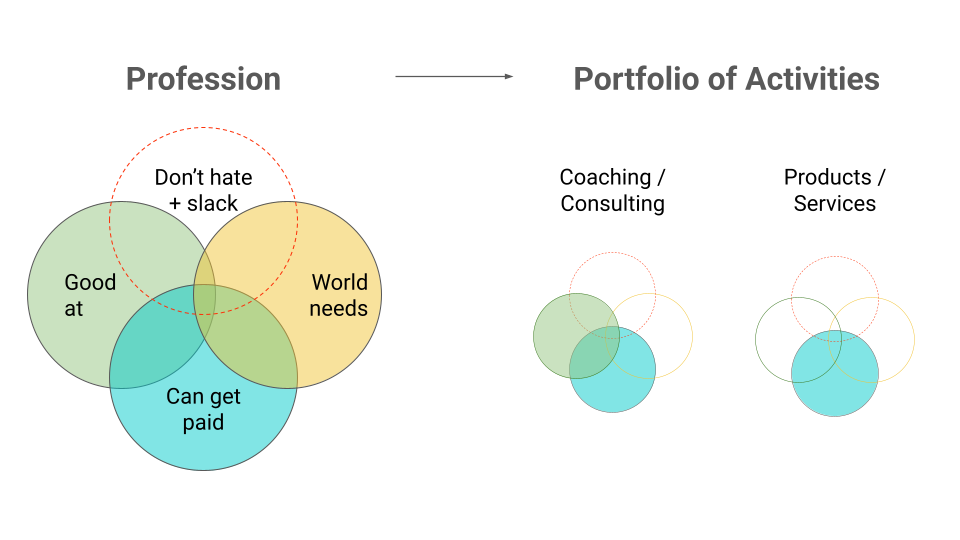

The meta-strategy is unbundling.

You first incubate a skillset inside a stable job, grow it into a profession, and then unbundle it into independent income streams. You are stripping parts off the corporate hull to build your own raft.

When you’re salaried, you’re generating more value than you’re paid. Go independent and you keep the surplus. Unbundling into multiple activities adds flexibility and resilience on top. As productivity increases, you reclaim the surplus. You buy back your time. Which raises the terrifying question: what do you actually want to do with it?

Sacred Art

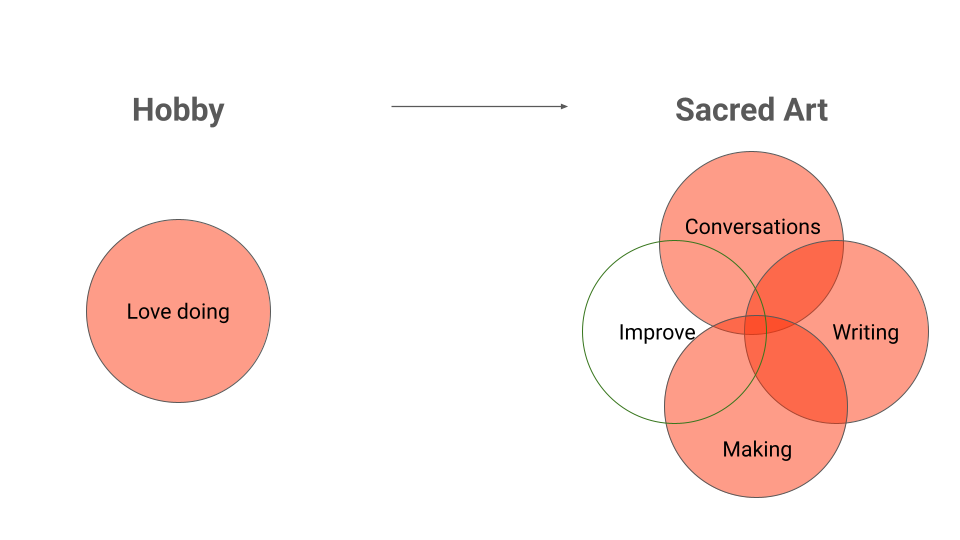

Intrinsic motivation is the cleanest fuel. If you are naturally fascinated by an activity, you will go deep with ease, where others must whip themselves into achieving half as much. The temptation is to arbitrage this flow into productivity.

Resist it. Because as soon as you make the activity about achievement (even if not monetary), the magic is gone. I face this in my writing practice. It’s hard not to optimise my writing for engagement. I really like to see those Substack numbers go up (please subscribe).

But something more important is at stake than adorning my ego with likes. It feels like some pieces want to be written. There’s an almost gravitational pull to certain topics. My saving grace is that I can’t actually predict which pieces will do well, so I usually go back to writing what feels alive.

But writing alone isn’t my sacred art. This essay is a braid. It started on a catch-up call with a friend that veered into career advice. What came out pulled on years of sitting practice, my own startup wreckage, and a stubborn hope about how life could be. That’s the Glass Bead Game: you pick up one bead and find it’s attached to everything else. Writing is just where the weave becomes visible. My sacred art lives in the intersection of the activities I love: the conversations, the contemplation, the making. The goal is to keep playing, not to sell the beads.

Intrinsic motivation is precious. It needs to be protected from the market, a universal acid dissolving everything it touches into a commodity. If you expose your art to the market, it will be corroded into “content”.

The monastery had walls for a reason: sacred spaces are demarcated, removed from ordinary economic logic. If your hobby is not just a way to pass idle time, it needs similar boundaries. I use “sacred” because it opposes the profane, where instrumental considerations hold.

JF Martel uses this frame to distinguish art from artifice. Art is created for its own sake. Anything else is artifice, the instrumentalized version of creation. Build the walls of your monastery in time. A zone free of monetization. This protected space transforms work into play, because there is no externally imposed goal. To practice a sacred art is to follow a gradient of aliveness while answering something that wants to exist through you. You keep adding threads until the weave could only be yours.

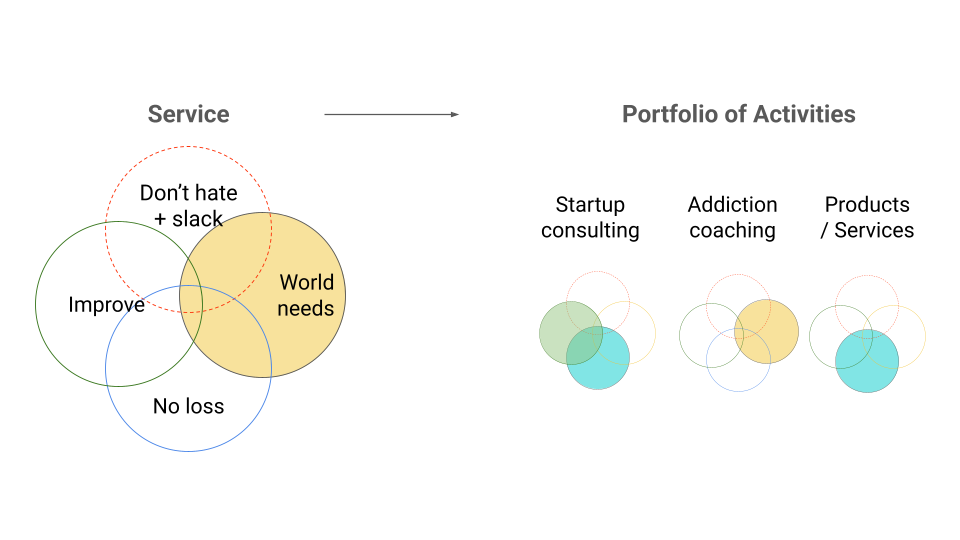

Service

But the monastery isn’t a bunker. Eventually, a true Sacred Art produces more energy than you can consume alone. You hit the point of overflow. When you aren’t trying to extract value from your art, you often end up creating value by accident. The insights you mined for yourself start looking useful to others. Service comes in as a release valve for the surplus.

I’m still figuring out the economic and artistic legs of the tripod, but the further I get, the more the desire to help others grows. After overcoming a substance addiction, I feel kinship with others who struggle with this, and a desire to help. Service seems to fade in slowly, and only rarely arrives as a holy mission. Contrast this with the moneymaxxing grindset: philanthropy only once you’ve “made it”.

The good news is that economic practice and service combine easily. At the very least, they can set useful constraints for each other. Just like we limited our economic activities to those who don’t do any harm, we can limit our service activities to those who don’t lose money. If a service activity makes an economic surplus, it becomes scalable (and much more impactful).

At the same time, you should be clear about priorities for each activity - is the main goal to make money or to help people? Don’t fool yourself. True service comes from overflow, not a compulsion to please your internalized father. When the surplus is real, giving it away just feels good. No martyrdom required.

You Can Have it All (but not all at once)

Don’t try to find a single activity that solves for financial success, artistic expression, and deep meaning. Chances are, it doesn’t exist.

Instead, unbundle. Go after them separately, and let them cross-pollinate over decades. Especially in the beginning, a clear separation between the different areas of your life is helpful for clarity and avoiding a muddy middle of bad compromises.

For most, the “money problem” takes precedence. Not requiring your profession to also solve for self-actualization makes the game much easier to win. You hit the landmarks sequentially: Economics, then Art, then Service. I’ve structured this piece around my own progression but some feel the call to service long before artistic expression. Start where you’re drawn.

You might be able to have it all in this life. But not in the same activity and not at the same time. The walls around the monastery have gates, and over time, the circles of your life will bleed into each other. But that is the end game, not the opening.

this was very relevant for me. I especially loved how you broke apart the incentive structures and spoke to sequencing. thank you!!

This article is great. Really